Before the industrial revolution, the CO2 content in the air remained quite steady for thousands of years. Natural CO2 is not static, however. It is generated by natural processes, and absorbed by others.

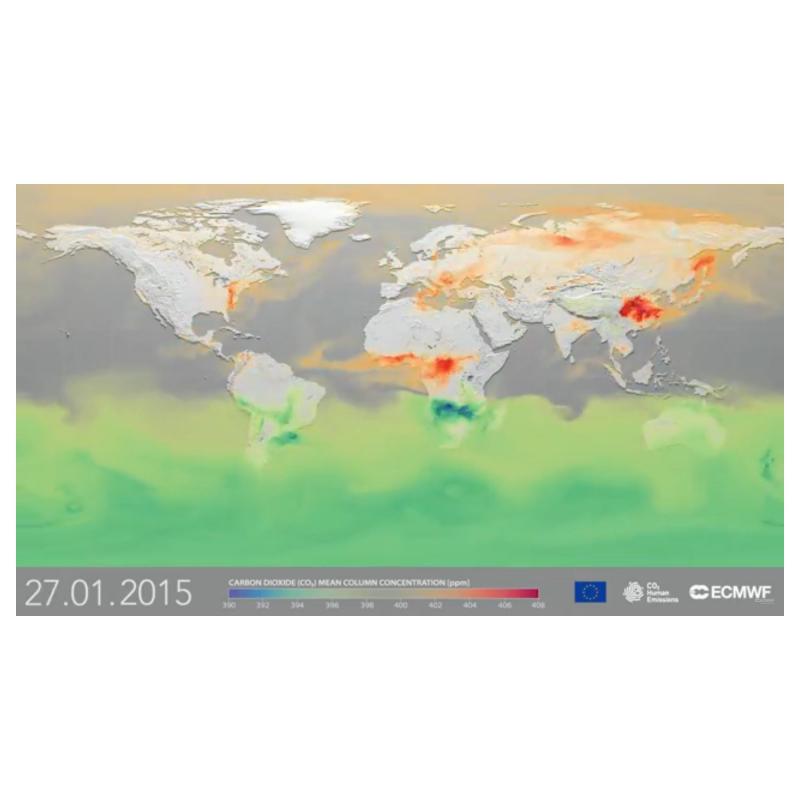

As you can see in Figure 1, natural land and ocean carbon remains roughly in balance and have done so for a long time – and we know this because we can measure historic levels of CO2 in the atmosphere both directly (in ice cores) and indirectly (through proxies).

But consider what happens when more CO2 is released from outside of the natural carbon cycle – by burning fossil fuels. Although our output of 29 gigatons of CO2 is tiny compared to the 750 gigatons moving through the carbon cycle each year, it adds up because the land and ocean cannot absorb all of the extra CO2. About 40% of this additional CO2 is absorbed. The rest remains in the atmosphere, and as a consequence, atmospheric CO2 is at its highest level in 15 to 20 million years (Tripati 2009). (A natural change of 100ppm normally takes 5,000 to 20,000 years. The recent increase of 100ppm has taken just 120 years).

Human CO2 emissions upset the natural balance of the carbon cycle. Man-made CO2 in the atmosphere has increased by a third since the pre-industrial era, creating an artificial forcing of global temperatures which is warming the planet. While fossil-fuel derived CO2 is a very small component of the global carbon cycle, the extra CO2 is cumulative because the natural carbon exchange cannot absorb all the additional CO2.